I've always loved computer games. When I was young, I got to play arcade games as they first came out. I remember when Pong was first installed in our local pinball parlor. I spent a lot of time in video arcades in high school. When I became an adult professional, I found that many of my colleagues had basically never played such games. And I played relatively few as I worked to establish my career.

When my children were little, I would often identify a game they were playing and play it with them. In part, this was to have a an excuse to do things with them. I often felt like my dad would let me participate in his world (going for a hike, birdwatching, etc.) but was never willing to engage with me about things I was interested in. I wanted to find something they were doing that I could stand. So I played Pokémon with them (they got Red and Blue while I got Pokémon Yellow — with Pikachu!). And the Zelda games. And a variety of others, along the way.

At the same time, I try to set limits. I generally only play one game at a time: I played Ingress until I decided to try Pocket Camp and played that until I switched to Pokémon Go (at the suggestion of a son). My goal is that playing games remains just a small part of my day.

We got a Gamecube as our first video console game when it was relatively new. And one of the first games we got was Animal Crossing. I was immediately charmed by the game: You arrive in a a new town and buy a house with a gigantic loan that you need to pay off by collecting stuff (fruit, then insects, then fossils, then fish, then art) and selling it to earn "Bells" — the currency. The guy who loans you the money (a suave business-tanuki) also runs the store that you buy and sell stuff at. But the game had a variety of creative touches: in particular there was a museum that would accept donations of one of each of everything to put on display. And some fish and insects could only be found at certain times of day, or certain locations on the map. Or certain seasons.

One of the best features was that it appeared to be intentionally designed to have you to play every day, but to play for only a relatively short amount of time. It gave decreasing rewards the longer you played in a particular session. Although you could "grind", you could do most of the stuff that needed to be done for the day in a half hour. You could pick all the weeds, collect all the fruit, etc, and then there just wasn't much to do. But you might want to check back at various times of day to see if different fish or insects were out.

After the GameCube, the kids moved on, and I hadn't played Animal Crossing for years. I never played "New Leaf" which was released for the Nintendo DS (which I didn't have). Two years ago, Nintendo released a mobile game called "Pocket Camp" which I played for a while.

When they announced the newest version in the franchise, New Horizons, I figured I might try it to see what it was like. But I wasn't particularly excited about it. Then the Coronavirus happened.

Animal Crossing has gotten a huge amount of press worldwide as people cast about for something to do during the quarantine. The best article I've read so far is The Quiet Revolution of Animal Crossing which describes the game as a thought experiment about how life could be organized along a different set of values, that maximizes happiness and freedom over profit.

In my five-person household, four of us are playing Animal Crossing together. My younger son, who is the only one who has a switch, was gracious enough to let the rest of us create houses on "his" island. It's been fascinating to me to watch how each of use apprehends and constructs a completely different reality about how to organize their in-game activity.

He was actually pretty unhappy at having to share his island -- and even volunteered to purchase another switch to avoid this fate. But it was too late: there were no longer any available for love or money. As the primary player, he was the one that had to spend money early in the game for any infrastructure and for the animal residents. And for a while, this added to his passive-aggressive relationship with the rest of us. But when he hit it big in the "stalk market," he became a bit less concerned with money.

My older son has been more interested in large-scale engineering projects to facilitate resource extraction: reshaping the landscape to improve the quality of fish and creating separated spaces for large orchards to grow fruit, or constructing giant fields of flowers to generate crosses to get different colors.

My wife, who was an avid player of pocket-camp, is entirely driven by the gamification. There is a second form of currency (Nook Miles) which you earn by accomplishing tasks. She structures her game play to maximize earning Nook Miles, so she generally sells things or buys things, not due to need or interest, but only when the system offers you a reward for doing so.

I think I understand my own perspective best. I approach the game as play. I am not particularly goal oriented, but enjoy moving through the game with serendipity finding things (like fish and insects) and trying improve the aesthetics of myself, my house, and the island. That said, I'm not above using the gamification features to somewhat restructure what I want to do: sometimes I identify things I want to buy and then wait to purchase them until there is a reward.

A brief digression about gamification: as has been amply documented, rewards undermine the potential for developing intrinsic motivation. A good in-game example is photographs. The game sometimes offers a reward for taking a photograph. So you can get the reward for just randomly clicking the button. And that's what my wife's photographs tended to look like. But the game offers a vast array of resources for taking *interesting* photographs. In fact, its pretty clear that the game designers realized that by enabling people to take photographs and share them via social media, they could give the marketing additional reach.

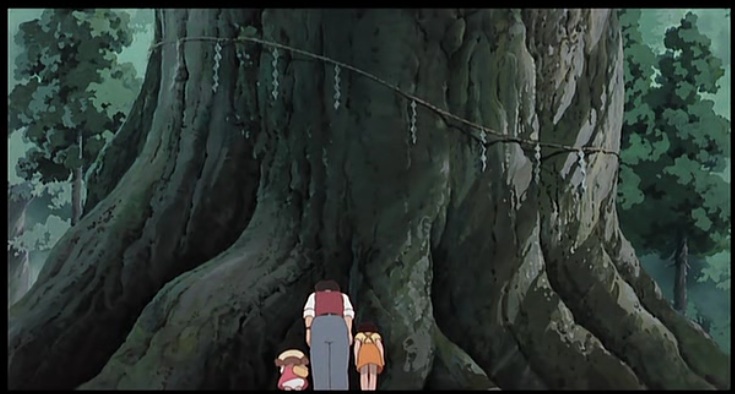

Looking at the pictures posted online, I notice a further division in the kinds of images posted. Some people share the ordinary events of the game: "Ooh! I caught a coelacanth!" Whereas others show some creative project they undertook: a labyrinth of tarantulas or my archaeological site (see below). Those are the only interesting ones, to me. Everyone experiences the ordinary moments of game play. But seeing something uniquely creative, like these wanted posters where Jolly Redd moors his boat.

I created a little archaeological site that I'm rather pleased with.

Nintendo even set up a place ("Photopia") where you can dress up rooms and characters from your island with all of your furniture and clothes to stage scenes to photograph. I discovered early on that this includes the avatars for other players. There's something deeply unsettling about being able to take another player's character, strip them to their underwear, and then dress them and pose them however you want. I mean, it's not R rated. But it still felt like a violation. (You can find these pictures and more at my Animal Crossing Image Gallery.)

As a further aside, I wish it was easier to get the image files out without posting them to social media. As far as I can tell, the only way to get them out is by removing the MicroSD card and copying the files by hand. I don't really want to give the switch (and anyone who uses it in the household) permission to post as me to social media. That's just not going to happen.

Animal Crossing is like a Rorschach test that causes each player to see different aspects. Some people see Animal Crossing as representing consumerism gone mad: go into more and more debt to expand your house and stick useless stuff in it! At the same time, there's no obligation to do that. The animals live very simply. Players have to opt in to the consumer culture. Nobody makes you take out larger and larger loans -- or even pay off the loans you have. There's no interest. You don't even need to build a house: you can keep just living in a tent, if you want.

I'm also playing as "girl" character which has been interesting. I never took much interest in clothing in the previous games: Your avatar had to wear something, so I'd pick some generic clothes and then basically never change them. As a "girl" however, I have skirts and blouses and sweaters and tights and shoes and am taking great delight in mixing and matching them. I also annoy people by saying things like, "It's not lady-like to run with tools in your hands."

The most difficult aspect, for us, has been reconciling our different perspectives on managing the island. This particularly came to a head when we all got the ability to terraform the island -- to add or remove water features and high ground. Who gets to make those decisions? When should you consult with others? Governance is hard work -- even for a game. We're still struggling with this. We've had a couple of passionate arguments about this, but have been able to work through them so far.

The multiplayer aspects have been particularly interesting to me. One multi-player mechanism is to visit other people's islands or let them visit yours. In this way, you can get things that are rare or not available on your own island. Or, if you're participating in the "stalk market" you can buy or sell turnips at more favorable prices. But there is also a cooperative game-play mode.

While playing, you can "tag in" other players who can share the screen with you while you play. But this means there is the single, shared screen. The camera keeps the main player on screen, but moves to try to keep the second player on screen. If they go too far, they unceremoniously pop back on to the screen. But the loss of sole control of the camera can be pretty frustrating and makes certain activities difficult or impossible without the active collaboration of the second player. For example, you can't reliably see fish to catch them without the connivance of the second player. Having realized this, I've taken this as a challenge, to co-play effectively in a supporting role. It's a unique dimension to game play that I hadn't considered before.